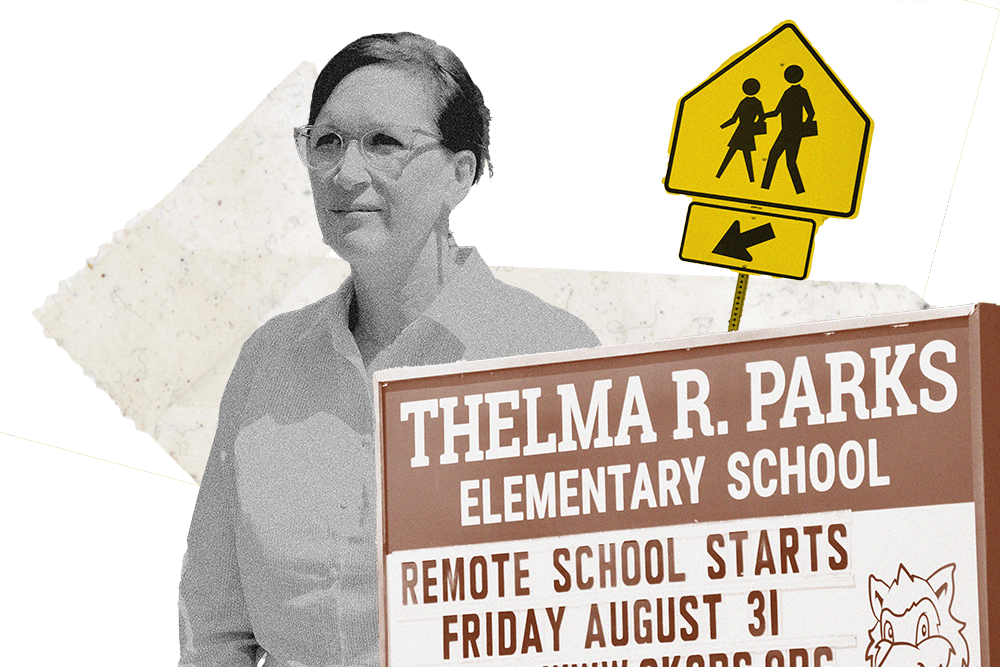

Wide-eyed and wearing a backpack too large for his nine-year-old frame, Trevor walked into the office at Thelma Parks Elementary in northeast Oklahoma City ready for another first day of school. It was mid-November, and while most of the other students were settled into classroom routines and already looking forward to the coming winter break, Trevor was enrolling in his fourth new school in four months.

“You knew this kid probably needed a lot to catch up, but you also knew we might only have this child for a few weeks,” said Michelle Lewis, the school’s principal.

A new student arriving or leaving midyear is a common reality at Thelma Parks, where 41 percent of students during the 2018-19 school year were not enrolled for the entire year.

Across Oklahoma City, an average of one in three students do not stay at the same school for the entire year, according to enrollment data analyzed by The Frontier and The Curbside Chronicle.