One year after Oklahoma lawmakers passed a bill banning some concepts about race in public schools, Bixby teachers decided to shelve a lesson on “Dreamland Burning,” a young-adult historical fiction novel based on the Tulsa Race Massacre.

A parent from the group Moms for Liberty had complained about the book during the previous year, although her son was allowed to read something else. The Tulsa County chapter of Moms For Liberty said in a statement they agree with the history of the Tulsa Race Massacre being taught but don’t support the idea that any person today is responsible for the event.

“We cried. I cried. The assistant superintendent cried. She felt awful,” Bixby ninth-grade history teacher Jaime Lee said.

Bixby administrators Rob Miller and Jamie Milligan recommended the educators teaching “Dreamland Burning” review the lesson and cautioned them that the district might be unable to protect teachers from punishments under Oklahoma House Bill 1775, like losing their teaching certifications. The district could also be penalized with an accreditation downgrade.

Miller told The Frontier he wasn’t concerned with the lesson’s content, but more with how state education leaders were interpreting the law after a vote to downgrade the accreditation status of Tulsa and Mustang Public Schools in 2022 for alleged violations.

Lee said her administrators were supportive throughout the review process. And, after considering potential consequences, she and her colleagues collectively decided to stop teaching the lesson.

Lee still teaches a nearly month-long unit on the Tulsa Race Massacre. But now she sends parents an email a week in advance so they can access her lessons and opt to have their children sit out of parts they aren’t comfortable with.

Two years after the passage of HB 1775, educators say a chilling effect has fallen on classrooms in teaching on complicated subjects like the Tulsa Race Massacre. The law includes an exception for material in state educational standards like the massacre, but four teachers told The Frontier they avoid some topics because they fear punishment.

In July, Oklahoma State Superintendent Ryan Walters drew international backlash when he said he supports instruction on the Tulsa Race Massacre, but he doesn’t think students should learn that the event is linked to inherent racism.

HB 1775 prohibits students from learning eight concepts about race and gender. The ban includes teaching that “an individual, by virtue of his or her race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist or oppressive” and that people bear “responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex.”

Putnam City North High School government teacher Aaron Baker has the eight concepts printed and pasted on the wall of his classroom to help him avoid violating the law.

Baker said he thought HB 1775 had no teeth until the State Board of Education’s vote to downgrade the accreditation status of Tulsa and Mustang Public Schools for violating the law. That, coupled with Walters’ campaign against critical race theory and calls to revoke a Norman teacher’s certification for sharing information on how to access banned books, has left some teachers petrified to teach complex historical topics.

Rep. Sherrie Conley, R-Newcastle, one of the authors of HB 1775, said the law is intended to prevent teachers from teaching critical race theory — which posits that race is a social construct and racism is embedded in systems that uphold racial inequality.

Conley said if there’s a historical consensus that the Tulsa Race Massacre was caused by racism, then teachers should feel safe to teach it without violating the law. She said students should be able to feel upset about what they learn regarding the destruction of the Greenwood district, but teachers shouldn’t tell white students to feel guilty about it.

Conley told The Frontier she thinks the Tulsa Race Massacre was motivated by race but hesitates to say the perpetrators were racist.

“It’s just a terrible tragedy in our state, and whether or not it was actually racism that caused the thoughts of the people that started it — we can try to speculate but to know for sure, I don’t think that we can,” Conley said.

Conley believes there’s a lack of understanding from teachers on what the law means. She said she thinks educators could benefit from training to clarify what they can and can’t teach about history and an analysis of their curriculum to ensure it doesn’t include banned topics.

Rep. Rick West, R-Heavener, another author of HB 1775, also told The Frontier he believed the law was needed to keep critical race theory out of Oklahoma classrooms.

“Critical race theory is not a good thing and it never will be,” West said. “We have to teach our history. We have to teach it no matter what, but we don’t add or take away from it. It should be taught. And the Tulsa Race Massacre should be taught because there’s lessons to be learned. We’ve got to know our history.”

But West said he didn’t know of any school districts where critical race theory is being taught.

What Oklahoma students learn about the massacre

Oklahoma’s academic standards have required education on the Tulsa Race Massacre since 2002. The standards require freshman and 11th-grade U.S. history classes to include lessons on the topic, without mandating any specific curriculum. History classes are required to examine multiple points of view regarding the evolution of race relations in Oklahoma.

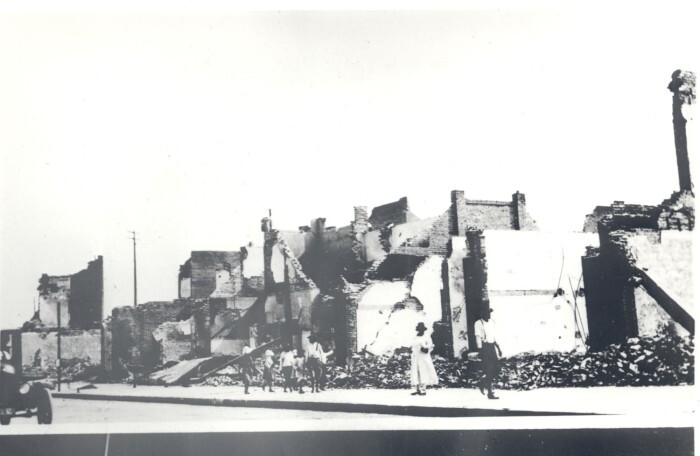

The standards were updated in 2019 to include the emergence of the Black Wall Street in Greenwood, the causes of the massacre and its continued social and economic impact and the role labels play in understanding historical events, such as past references to the destruction of Greenwood as a riot instead of a massacre.

The state department paired these with a resource for teachers in 2020 to help clarify the standards and provide recommendations for things like lesson plans.

Walters said in July he is continuing to work to develop an “even more robust curriculum” around the Tulsa Race Massacre. As state superintendent, Walters can suggest changes to Oklahoma’s academic standards, but he cannot mandate a specific curriculum or dictate how teachers should teach the standards.

The Frontier reached out to Walters multiple times asking for clarification on what changes he hoped to make and didn’t receive a response before publication.

Emily Harris, the K-12 social studies academic content manager for Tulsa Public Schools, said Tulsa’s curriculum surrounding the Tulsa Race Massacre hasn’t changed since the passage of HB 1775.

Third-grade students learn about discrimination and segregation in Tulsa by watching an animated version of the Dr. Seuss story “The Sneetches.” They also read the book “Up from the Ashes,” which talks about the development, destruction and rebuilding of Greenwood from a child’s perspective.

Sixth-grade students learn about the gentrification of Black Wall Street in geography. Eighth-grade Oklahoma history students learn about racial violence in the Tulsa Race Massacre. High school students in U.S. history analyze cases of racial terror after World War I, including the Tulsa Race Massacre. Students also tour the Greenwood Rising Black Wall St. History Center, which was established in honor of the massacre’s centennial in 2021.

Tulsa historian Hannibal Johnson, author of “Up from the Ashes,” who also served as a curator for Greenwood Rising, said it’s impossible to teach about the Tulsa Race Massacre without including its root in systemic racism.

“This ideological notion of white supremacy and black subordination is ultimately at the root of these events,” Johnson said. “We shouldn’t be afraid to acknowledge that horrific history, because if we don’t first acknowledge it, we can’t begin to remediate.”

But some teachers have become more cautious about what they include in their instruction about topics like the massacre since the passage of HB 1775.

At Union Public Schools, ninth-grade Oklahoma history teacher Will Buffington said lesson planning has become a more careful process for him and others in his department. They worked together to ensure lessons didn’t include things people could misconstrue as breaking the law ahead of time so they could address potential misinterpretations.

When Shawna Mott-Wright graduated from Daniel Webster High School in 1998, she knew about the Tulsa Race Massacre when others in her Oklahoma State University courses didn’t because of her Tulsa Public School teachers. Now, as a Tulsa Public School teacher and president of the Tulsa Classroom Teachers Association, she said she has spoken with educators who have quit over HB 1775.

“Because of all of the rhetoric surrounding it, they’re afraid they’re going to inadvertently say or do something wrong,” Mott-Wright said.

As Mott-Wright prepares to send her daughter back to a Tulsa Public School this August, she worries about what long-lasting effect the law will have on students.

“If we don’t learn about history, we are doomed to repeat it,” she said. “Some people are out there spouting some nasty, hateful rhetoric, and maybe they want it repeated. But most of us don’t.”

A law with far-reaching consequences

In 2021, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit against defendants including former Attorney General John O’Connor, former State Superintendent Joy Hofmeister and the state Regents for Higher Education, arguing HB 1775 limited the First Amendment rights of teachers and students. Anthony Crawford, an Oklahoma City English teacher who asked that his district not be named because he’s not authorized to speak on its behalf, was one of two teachers who joined as plaintiffs.

When he first learned about the law, Crawford asked a district administrator about its impact on his teaching. The administrator reassured him he’d be safe if he stuck to the state standards, which provide some flexibility in how he teaches his material.

But Crawford said he’s gradually noticed a loss of classroom control. He said he’s been asked by his superintendent to leave books out of his classroom like “Powernomics: The National Plan to Empower Black America,” which analyzes racial inequalities in the United States and how Black Americans can become more economically and politically competitive, and “Post-Traumatic Slave Syndrome: America’s Legacy of Enduring Injury and Healing,” which argues slavery and continued oppression has caused psychological trauma across generations.

Crawford said he believes these books helped students build arguments and connect classroom material to their personal experiences. Now he’s signed onto the lawsuit because he fears his teaching certificate could be revoked.

“I probably put myself in a bad position but in the greatest position ever,” Crawford said.

John Waldron, D-Tulsa, taught history at Tulsa’s Booker T. Washington High School for 20 years. Waldron said he always took teaching the Tulsa Race Massacre seriously, working in a minority-majority district and in a building that survived the massacre.

But Waldron said he now fears for the future of teachers covering difficult subjects.

In 2022 the State Board of Education voted to downgrade Mustang Public Schools’ accreditation after a complaint that a middle school student felt uncomfortable being asked questions in a team-building activity whether anyone in the room ever experienced discrimination.

Waldron said the punishment could have fallen on just the teacher, who could have taken a warning and changed her lesson plan. But instead, the State Board voted to downgrade the school district’s accreditation. This lower accreditation means the district is subject to extra state oversight and indicates a district failed to meet standards in a way that “seriously detracts” from the quality of its educational program.

And now there’s a delay in Tulsa Public Schools’ accreditation status until the Board of Education’s Aug. 24 meeting. Walters claimed the district “intentionally misled the department about funding spent on diversity, equity and inclusion programs.”

“HB 1775 has been weaponized by this superintendent and the State Board of Education, appointed by Governor Stitt, to go after entire school districts, and the effect will be to intimidate teachers in just about every classroom,” Waldron said.

Since HB 1775, Milligan said Bixby administrators talk a lot more about how they can support teachers amid legislation endangering their teaching certifications. They’ve sought to find a balance between helping them teach state standards safely and accurately while allowing them to maintain autonomy and enhance student engagement.

Miller said they’re cognizant that although they want parents to have a voice in their child’s education, it only takes one complaint for them to circumvent the district to go to the State Board, who can take action without giving districts much recourse.

“There’s no way to defend ourselves, and that sort of makes you feel like you’re walking on eggshells a little bit,” Miller said. “I know these teachers feel that way too because they’re passionate about what they teach. They’re not trying to indoctrinate kids. They’re trying to help kids become open-minded critical thinkers about all the perspectives associated with a historical event.”

Lee said she makes it a priority to build trust with her students to teach complicated topics. But HB 1775 and the current political climate in education have prevented her from being completely open with her students and engaging in conversations on political issues that naturally come up in a history class.

She fears she could lose her job if a parent misunderstood her intentions. Instead, she tells students to come back and talk to her after they’ve graduated.