After four years of annual reports the general public no longer has access to a detailed accounting of how nearly 200,000 tons of waste produced by Oklahoma’s Poultry Feeding Operations is exported or applied on state lands, including sensitive watersheds.

The Oklahoma Department of Agriculture Food and Forestry produced fiscal-year reports starting in 2015 but suddenly announced this winter its 2019 poultry waste movement report “compiled as a courtesy” would not be published. The Arkansas Department of Agriculture continues to produce its calendar-year report, normally issued in January but delayed this year due to COVID-19. An Arkansas official said that report also is compiled as a public courtesy.

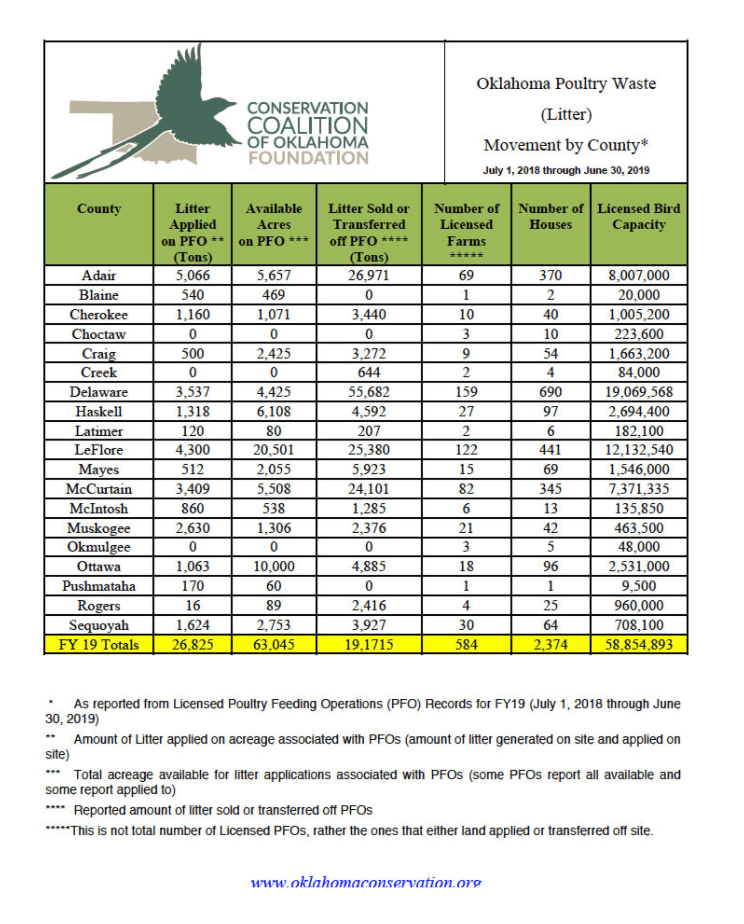

The reports detailed county-by-county applications of poultry waste applied as fertilizer and laid out statistics on the materials produced and applied within the sensitive Eucha-Spavinaw and Illinois River watersheds.

Oklahoma Department of Agriculture officials said data used to compile the reports would be made available to the public via simple requests, but the Conservation Coalition of Oklahoma Foundation discovered the information provided was incomplete, confusing and showed the environmental division of one of the nation’s top agriculture states relies on reporting methods for a known pollution source that are out-of-date and inconsistent.

In fact, officials noted the tedious, time-consuming process required to compile the report from department records was part of the reason it was discontinued.

Tulsa water source data restricted

Nonetheless, the Foundation attempted to create a report on the public’s behalf. It compiled the available information in a format similar to past reports but apples-to-apples comparisons proved impossible given the imprecise information on tons of applied poultry waste.

Moreover, data for the Eucha-Spavinaw watershed, which supplies fresh water to the City of Tulsa, was not provided at all. The Foundation was told it would require court action to obtain the information despite it being provided in previous reports.

Staff and budget cuts, and a project underway to digitize operations and improve the Department’s web site, as well as the Covid-19 pandemic, all were reasons listed for elimination of the report.

“The Department of Agriculture budget has been cut more than any other state agency and it’s likely there are more cuts coming this year,” said Agriculture Department spokeswoman Morgan Vance. “There are no rules related to producing the litter report. It is information that is submitted for regulatory purposes and it is open and available to anyone who requests it.”

Ed Brocksmith, founder of Save The Illinois River, a member organization of the Foundation’s sister Coalition, has collected the annual litter reports issued by Oklahoma and by the Arkansas Department of Agriculture and tracked production and application trends.

“We all know that non-point source pollution is a big issue and phosphorus from chicken litter used as fertilizer is an important part of that picture,” he said. “But what information do we have to help people understand that picture? Very little.”

Environmental Management Services Director and ODAFF General Counsel Tena Gunter said the nature of the data and demands on staff simply no longer allow time for compiling the report.

Click to read the CCOF Litter Report, download the ODAFF files and review the ODAFF Poultry Waste Reports for 2015-2018.

‘A tedious affair’

Former Environmental Services Director Jeremy Seiger compiled all the reports. His position and that of a program manager were both eliminated and Gunter now is general counsel for the Department as well as Environmental Services director.

In a 2019 interview Seiger told a Tulsa World reporter that compiling the report was “a tedious affair” and that it generally came together over the course of about two weeks, among other demands.

Poultry Feeding Operations and waste application companies are required to report details about chicken litter chemistry, the amount of waste produced, the amount that is spread on the Poultry Operation’s lands as fertilizer, amounts hauled elsewhere in Oklahoma or out-of-state and whether it is applied in one of Oklahoma’s protected watersheds.

Compiling the report was indeed tedious, Vance said.

“That’s part of why our entire agency is going all-digital and the web site is being redesigned,” she said of an effort underway since March of 2020. “We will have an online tracking system that will allow people to make payments online and submit poultry reports, among other things. In the past we had hand-written reports that had to be input by our staff, so the new system will cut down on input errors and staff time.”

Still, the hodgepodge nature of the data leaves little hope for resurrecting the reports.

Fertilizer haulers report poultry waste application locations by range, township and section. However, Poultry Feeding Operations report the sources of litter and their own applications using latitude and longitude coordinates.

Some fertilizer haulers note application on land sections that are literally split by watershed boundary lines. Without knowledge of the area and where the litter was applied a report for the watershed could easily be off by several tons.

The Department of Agriculture compiles information based on a July-through-June fiscal year, but the state of Arkansas, and a court-ordered requirement for the entire Eucha-Spavinaw Watershed all are based on calendar-year reports. That is problematic because both the Illinois and Eucha-Spavinaw watersheds straddle the Oklahoma/Arkansas state line.

Gunter acknowledged that a reporting system overhaul with a requirement to report applications by watershed would help ODAFF staff but she doubted it would work as a practical matter.

Watershed-specific information needed

“Watersheds don’t follow county lines or townships,” she said. “Most of these guys aren’t going to know what watershed they’re in and the statute does not require they report by watershed.”

However, watershed maps are readily available through the Oklahoma Water Resources Board website. The Foundation imported OWRB shape files to Google Earth and quickly plotted application locations at no cost. Many mobile device apps used by hunters and backcountry hikers show property lines, trails, hunting zones, public lands boundaries and are capable of importing other map layers.

“That’s always been the difficulty,” Gunter said. “If the Legislature had required us to get that information in our reports as they are submitted that would help and we could rely on that. People would just have to learn their watershed.”

Rep. Meloyde Blancett, D-Tulsa, introduced a bill, HB 2719, this session that would, in part, call for watershed-based reporting of litter applications, but she said last week that the bill was essentially dead on arrival.

“There is huge pushback on any effort to tighten reporting or legislative language around it,” she said. “I am not anti-poultry industry, I am for ensuring our industries can continue while protecting our most precious commodity, which is fresh water. We demand that (Poultry Feeding Operations) report this information but what are we doing with it for their benefit or for the benefit of the general public? If you are a resident of this state and you ask for the information all you get is a massive data dump that would take a university professor to figure it out.”

Inability to access the previously published Eucha-Spavinaw information, credited in past reports to “the Eucha-Spavina Group,” remains a puzzle. Agriculture Department Assistant General Counsel Shelby Turner said the information would have to be obtained through the United States Northern District Court of Oklahoma.

Attorney Lou Reynolds of the Tulsa firm Eller & Detrich confirmed that while a 2003 court settlement made the information available to the Tulsa Metropolitan Utility Authority for its purposes, the information is not available publicly and the Special Master appointed to oversee the information is under a gag order not to speak to the media or release the information to anyone.

He said he could not explain how that information might have been obtained or what the “Eucha-Spavinaw Group” might have supplied to the former director.

“I suspect that if you want to know the Agriculture Department has all the information, you just have to find a way to get it from them,” he said. The Foundation posted the Report—as best as it could produce—plus all of the past ODAFF reports and materials used to produce the new report on its website at oklahomaconservation.org and on its social media platforms.

Kelly Bostian is a conservation communications professional working with the Conservation Coalition of Oklahoma Foundation, a 501c3 non-profit dedicated to education and outreach on conservation issues facing Oklahomans. To support Kelly’s work please consider making a tax-deductible donation at https://www.oklahomaconservation.org