A neighbor found Brent Thurman lying in a parking lot in the summer heat and unable to move after he sought care at two Tulsa hospitals. But neither medical center will face consequences after a federal investigation cleared them of wrongdoing.

More than a year later, Thurman lives in a nursing home and still can’t walk.

After emergency responders took him by ambulance to a third hospital in July 2022, Thurman needed emergency surgery for an infection that had spread to his neck and blood, he said.

“You don’t know how much pain I’m in every day,” Thurman, 42, told The Frontier recently while sitting in a wheelchair. “I feel like it’ll never go away.”

Acting on a complaint, federal authorities launched an investigation into whether Oklahoma State University Medical Center and Hillcrest Medical Center violated a federal anti-patient dumping law for failing to treat Thurman, who was experiencing homelessness when he sought care at their emergency departments.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services sent both hospitals letters in May stating that inspectors had found the facilities were in compliance with federal rules after a review of records and interviews with staff.

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act requires hospital emergency rooms that participate in Medicare to screen and treat everyone with an emergency medical condition, regardless of ability to pay.

Hospitals that violate the law can be fined and excluded from participating in Medicare.

But it’s rare for hospitals to face financial penalties, said Barbara DiPietro, the senior policy director with the National Health Care for the Homeless Council. When hospitals are fined, about one in five cases are for people with a mental health condition.

“It’s a high threshold,” DiPietro said. “…Hospitals have a lot of political relationships, as well, and to sanction a hospital is not a small thing to do.”

Hillcrest and OSU medical centers said they could not answer questions about Thurman’s case because of patient privacy laws.

“While we are pleased state and federal regulators found our hospital to be in compliance with all regulations relating to this incident, we take our responsibility to care for all individuals — including those experiencing homelessness — very seriously,” Hillcrest said in a statement.

OSU Medical Center said in a statement that it has “a long history of providing fair and equitable care regardless of the ability to pay.”

Dumped during summer heat wave

Julie Bennett started bumping into Thurman after moving into her downtown Tulsa apartment in 2021.

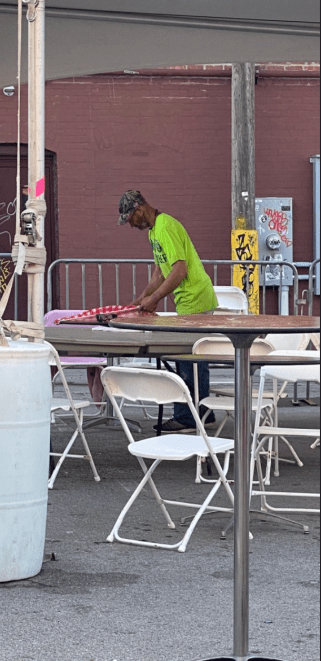

Thurman slept in the nearby parking lot, and spent his time picking up trash and guarding tenants’ cars at night against break-ins. Sometimes Bennett and Thurman would say hello. Occasionally she’d bring him food. Last summer, Bennett and her husband saw Thurman with what they thought was a broken wrist. He’d had his belongings stolen and got into a fight, he said.

They brought him a sling, and a few weeks later decided they should call an ambulance as his hand swelled. Thurman went to nearby OSU Medical Center, but said the hospital wouldn’t treat him because of a previous incident at the emergency room where he was escorted out by security, he said. The hospital said it couldn’t respond to questions about the incident.

He limped back to the parking lot where he slept.

For the next few days, Bennett and other neighbors brought ice and Gatorade to Thurman. It was the hottest week of the year in Tulsa, with temperatures that soared up to 107 degrees. Bennett batted away flies swarming around Thurman’s body.

“He was all balled up and crying and just couldn’t move,” Bennett recalled. Neighbors called another ambulance that took Thurman a mile and a half away to Hillcrest Medical Center.

Thurman can’t remember all the details of his time at the hospital, but said a nurse told him to get into a wheelchair. When Thurman said he couldn’t walk, the nurse pulled on his arm to get him into the chair as a security guard waited nearby.

“I think they thought I was on drugs,” Thurman said of the incident. “But I wasn’t.”

Security guards ultimately wheeled him across the street from the hospital and dumped him out onto the sidewalk in the middle of the night, Thurman said. A surveillance video first reported by The Tulsa World shows a person being dumped out of a wheelchair onto the sidewalk the same night. He laid there until a friend came the next morning, loaded him onto an orange flatbed dolly and pushed him back to his parking lot.

Bennett was shocked to see Thurman again when she walked to her car in the morning. He was lying next to the dolly in the parking lot and couldn’t use his hands or talk.

A maintenance man from Bennett’s building called another ambulance a few hours later to take Thurman to a third hospital, Saint Francis. Bennett met Thurman at the hospital and waited with him for several hours in the emergency room. When nurses began to examine Thurman, they tried to get him to get out of a wheelchair and have him stand, Bennett said. Thurman said he couldn’t, but nurses insisted he could. Bennett eventually intervened.

“I was having to explain to them what my observations were of Brent the last several days and weeks because he just couldn’t explain it,” Bennett said.

Hospital staff determined it was a severe infection and pulled Thurman into emergency surgery. He spent the next few months in and out of intensive care, at times relying on a ventilator and feeding tubes.

The infection left his arms and legs paralyzed, and another infection flare up this year sent him to the hospital for several weeks in August.

Anti-patient dumping law often applied broadly

Inspectors from the Oklahoma State Department of Health visited OSU and Hillcrest in July and August 2022, records show.

The federal government relies on local investigators to conduct unannounced walkthroughs, review records and interview hospital staff to investigate complaints.

The goal of inspectors is to investigate complaints and whether a facility is in overall compliance with state and federal regulations, said LaTrina Frazier, a deputy commissioner who oversees hospital inspections for the Oklahoma State Department of Health.

Federal guidelines say investigators can interview patients and witnesses, but Thurman and Bennett said no one ever contacted them.

State investigators send their findings to the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for a final ruling on whether a hospital violated anti-patient dumping rules.

The Frontier filed a Freedom of Information Act request for all of the records from the investigation, but the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services only released four pages of documents, including two short inspection reports that found no deficiencies at either hospital. The agency did not respond to questions about whether it reviewed the video that allegedly shows Thurman dumped on the sidewalk.

Rade Vukmir, a doctor with the American College of Emergency Physicians, said the law is often applied too broadly by those who file complaints against hospitals. If a hospital examines someone and provides medical care for an emergency condition, then they’ve met the intent of the law. Federal guidelines say hospitals can’t be held liable for misdiagnosing a condition if they used all of their resources during a medical screening, which can range from a brief physical exam to laboratory tests and other diagnostic tools. Concerns about medical negligence or discharge procedures should be separate issues, he said.

Patients can sue for medical negligence, but that requires finding a private attorney, which can be a challenge for people experiencing homelessness.

Thurman was raised by his grandmother until she died when he was 12, he said. Then he was in and out of foster care and living on the streets in Tulsa. He had stints in prison and jails. Thurman can’t read well and didn’t go to school as a teenager, he said.

An attorney dropped Thurman’s case after several months and never filed a lawsuit on his behalf.

Tulsa hospitals discharge a growing number of patients to the streets

The number of people discharged to homelessness from emergency departments in Oklahoma is growing, according to data from the State Health Department. Hospitals sent some people back to the streets or to shelters that aren’t equipped to handle their medical needs.

In 2022 alone, emergency departments made more than 2,000 discharges to homelessness in Tulsa County — nearly four times as many as in 2020 when the state began collecting data, according to provisional figures from the State Health Department. Tulsa County residents had the most discharges to homelessness in the state in 2022.

During the height of the pandemic, the City of Tulsa used federal coronavirus relief funds for a medical respite facility for people experiencing homelessness. The facility served hundreds, but once the federal funding ran out, the program was closed.

Hospital administrators say they provide care to everyone who needs it, but that hospitals aren’t the right place for someone to stay if they don’t need acute medical treatment. This can create tension between shelters, hospitals and patients. Most hospitals employ social workers who try to coordinate discharge plans, but many individuals say they have been turned away from care or discharged early to homelessness.

As visits to emergency departments are increasing nationally, staffing shortages have led to longer wait times and violence in emergency departments has increased, according to the American College of Emergency Physicians.

The federal Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General settled a case similar to Thurman’s with a hospital in Alabama in 2018 for discharging a man who was “reportedly aggressive and non-compliant with staff directions.” A hospital security guard placed the man in a wheelchair and left him on the ground off hospital property. The man was found unresponsive and later died.

Hospitals are required to screen for emergency medical conditions, which the federal government defines as being so severe that delayed medical care could be “reasonably expected” to put a person’s health in serious jeopardy. Hospitals are required to stabilize those that need treatment.

That requirement stands even if someone is disruptive, said Rich Rasmussen, president of the Oklahoma Hospital Association. But hospitals sometimes call police or have security guards remove patients for being disruptive or violent.

But what’s considered disruptive can be subjective, said Lisa Dailey, executive director for the Treatment Advocacy Center, which supports better access to care for people with severe mental illness. Some hospital staff might see people experiencing homelessness or those in a mental health crisis as just looking for a place to sleep or trying to get drugs.

Hospital staff should be trained in de-escalation strategies and have the resources to handle upset patients in emergency rooms, Dailey said. A 2014 report from the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights recommended more oversight from federal regulators and increased data collection and training for hospitals.

“If you don’t have appropriate training, it’s almost inevitable that you’re going to be influenced by the fact that a person who’s in a crisis can be very difficult,” Dailey said.

Hillcrest said in a written response to The Frontier that it created a committee in 2022 to better address disruptive patients or threats of workplace violence. The hospital also offers bus passes or rides to shelters and has a social worker and patient advocate in the emergency department.

Focusing on healing

For the last year, Thurman has lived in a nursing home tucked in the trees a few blocks from the Arkansas state line.

It’s a bright facility with deck games on the front porch and a cafeteria with greenery painted on the walls. A large living room area broadcasts black-and-white movies for residents. Thurman doesn’t pay attention to them though, he said.

When he first got to the nursing home, he was mean and angry. But he’s made friends with the nursing staff now and feels more comfortable.

Sometimes he sits on the porch in his wheelchair. Bennett and other friends visit when they can, bringing Dr. Peppers as a treat. Thurman recently had his 42nd birthday party at the nursing home. He does physical therapy. He says he often thinks about his time at the hospitals last summer.

He was scared when he woke up from surgery with tubes and monitors hooked up to him. He’ll likely have to take antibiotics for the rest of his life. Sometimes he gets so sick, he has to go back to the hospital. Doctors want to perform another surgery, but Thurman worries about complications.

“Some of the stuff makes me mad, and some of the stuff I get used to,” he said. “It’s pretty bad that it happened.”

Bennett is arranging for a volunteer to help Thurman improve his reading ability. She also helped Thurman connect with family members. By next year, Thurman hopes he’ll have regained enough mobility to walk.

“My hope would be that he could eventually get out of the nursing home and have enough mobility that he can move around in a wheelchair and just participate in life,” Bennett said. “Build relationships. Have healing, fulfillment.”